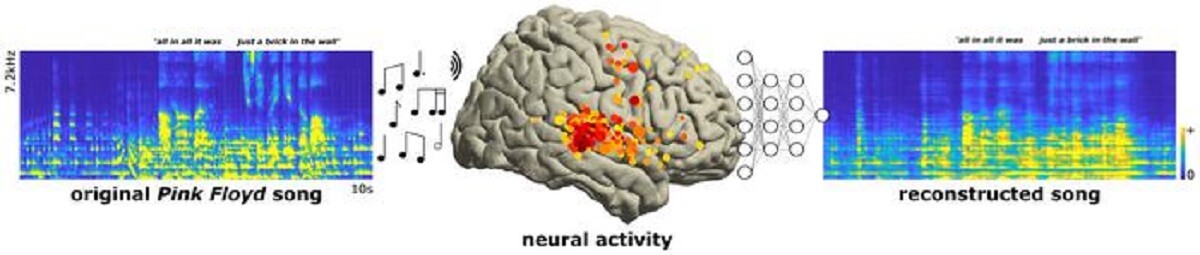

BERKELEY, Calif. — A unique rendition of a classic Pink Floyd track has been created — using brain activity recorded while people listened to the song. Utilizing cutting-edge techniques, scientists created an innovative “remix” of “Another Brick in the Wall” and identified a novel brain area essential for understanding musical rhythm. Interestingly, researchers from the University of California-Berkeley believe this may pave the way for the creation of improved prosthetic limbs.

Listeners can discern the iconic line, “All in all it was just a brick in the wall,” in the reimagined song. The reconstruction, scientists argue, demonstrates the possibility of capturing and translating brainwaves into musical elements of speech, including rhythm, stress, accent, and intonation – collectively referred to as “prosody.” These elements add layers of meaning beyond just words.

This groundbreaking study was spearheaded by Dr. Ludovic Bellier, a senior computational research scientist at UC Berkeley. The research sheds light on our understanding of music’s cognitive processes.

“Decoding from the auditory cortices, which are closer to the acoustics of the sounds, as opposed to the motor cortex, which is closer to the movements that are done to generate the acoustics of speech, is super promising,” says Dr. Bellier in a media release.

While past studies have employed computer modeling to decode and reconstruct speech, a comprehensive model accounting for musical attributes like pitch, melody, harmony, rhythm, and the diverse brain regions involved was missing. The team addressed this gap by applying nonlinear decoding to brain activity from 2,668 electrodes positioned directly on the brains of 29 volunteers as they enjoyed classic rock. Of these, 347 electrodes, mainly found in three specific brain regions, captured activity related explicitly to the music.

The team’s further analysis revealed that removing electrodes from the right Superior Temporal Gyrus (STG), an area attuned to rhythm, had the most significant impact on song reconstructions.

While the cutting-edge technology in this study can only record from the brain’s surface, it offers hope for aiding those with communication challenges resulting from conditions like strokes. Current robotic-sounding reconstructions lack the natural musicality of speech, and this research could change that.

“As this whole field of brain machine interfaces progresses, this gives you a way to add musicality to future brain implants for people who need it, someone who’s got ALS or some other disabling neurological or developmental disorder compromising speech output. It gives you an ability to decode not only the linguistic content, but some of the prosodic content of speech, some of the affect,” says Professor Robert Knight, a neurologist who collaborated with Dr. Bellier.

He emphasizes that while current non-invasive techniques remain imprecise, the hope lies in improving technology to capture deeper brain activity with clarity. In their previous collaboration in 2012, Dr. Bellier and Prof. Knight became pioneers in reconstructing heard words solely from brain activity. For this study, they reexamined brain recordings from 2012 and 2013, during which volunteers listened to a segment of the Pink Floyd song.

Validating established notions, the researchers found the right brain hemisphere is more attuned to music, whereas the left is inclined toward language. This distinction isn’t exclusive to speech, but is fundamental to the auditory system, processing both speech and music.

The study is published in the journal PLOS Biology.

You might also be interested in:

- Best Guitar Solos Of All Time: Top 5 Rock Music Moments, According To Fans

- Revolutionary AI mixing app creates mind-blowing musical mashups with your favorite artists

- Just 30 seconds of Mozart calms brain regions linked to seizures and epilepsy

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.